‘Stop thinking!’ Sion yells. ‘Don’t think!’.

I duck under his cross, then step in with a rear hook to the side, the punch supposed to crack the floating ribs. Sweat leaks into my eyes. ‘Your body knows what to do’ he’s shouting, as he calls out a combination. Slip. Hook. Underneath. Cross. Over and over and over, until time collapses.

I’ve been boxing for more than a year now. Even writing that sentence surprises me. Last year, Caroline – who we all love - set up a local group for women aged forty-and-over to learn to box with a professional coach. Each Wednesday night, around ten of us meet in a decrepit community hall (the men boxers have the big room; we are relegated to the small one at the back). We drill our jabs and hooks, practice our feinting and footwork. There is a lot of skipping.

And afterwards, my boxing friends and I swagger, giddy and flushed, out into the dark and empty suburban streets, our kit bags slung over our shoulders like a secret. We give thanks for the many ways boxing is saving us amid the stresses of mid-life: our jobs, our caring responsibilities, our relationships, and now also the gathering storm of our roiling hormones. Surges of anxiety, rage and grief can pull us under without warning. As boxers, we feel strong.

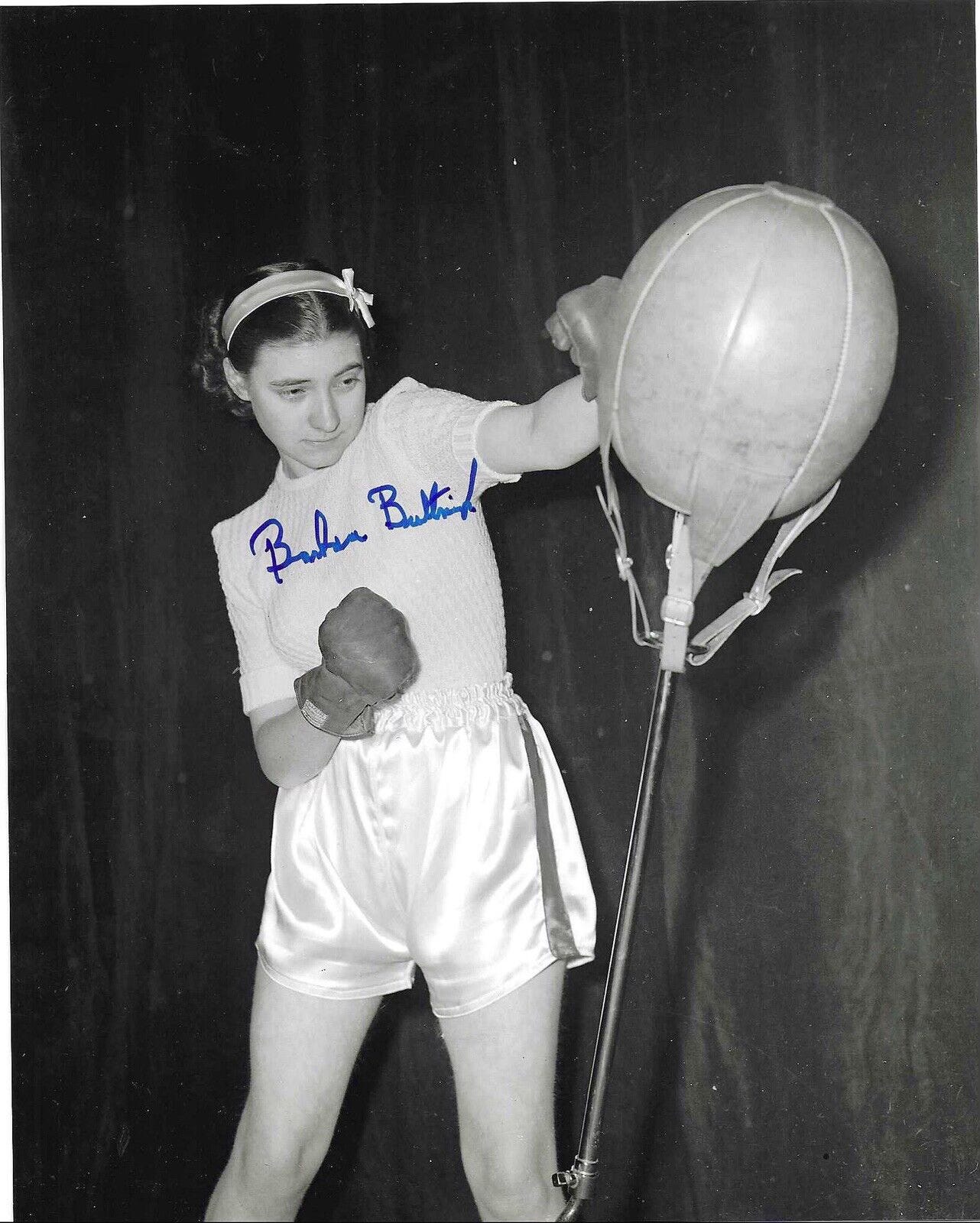

Barbara Buttrick, or ‘The Mighty Atom’, b. 1929, world champion and trailblazer of women’s boxing in the 1940s and 50s.

One of the places I am drawing on this strength is trying to finish writing my book about friendship. Joyce Carol Oates said writing is like boxing. A bloody fight to the death in the ring, only one person left standing (the writer hopes it is her; the book vanquished).

It’s true, sometimes writing does feel like a fight. Right now, I’m sprawling on the canvas after a tough week, the book looming over me, counting me out. I get back on my feet, swaying and try to focus.

Sure. Why not?

But really, it’s less grandiose. My theory is that awkwardness, not triumph, is the real reason boxing is like writing.

‘Don’t think!’. Sometimes I get there. Everyone around me disappears: the other boxers, Sion, all the people in my head who say I look stupid (even Carol Oates herself, who said female boxing is ridiculous: ‘Boxing is the obverse of the feminine. It is for men, and it is about men, and is men’ she declared.) Everyone leaves the room. And then I leave the room. And what is left is my body, performing what it has learnt.

But most of the time, it’s not like that. It’s all snag and clumsiness. It’s me, adjusting my stance, moving the weight from one leg to the other, dropping a shoulder. It’s self-conscious. It’s awkward.

Awkwardness, writes the critic Adam Kotsko, is being caught between two worlds, unsure how to behave in either. Awkwardness is being at a party with people whose lives are very different to our own, and feeling out of place. It’s being made to perform some public role we haven’t rehearsed for, unsure where to stand or how to act. Awkwardness is speaking in a tongue you have not mastered, or doing a dance you don’t yet know. It’s a date with uncertainty. But also with possibility.

Feeling awkward is how you know you’re changing.

Mostly, my boxing friends and I say boxing helps because we are learning something new. We don’t have to be good here. No one is depending on us. We can simply practice failing and trying and failing again. Feeling safe to fail and try again gives us courage, an antidote to the brittle world of performance metrics and outcomes. An alternative to the fragility of modern parenting and self-optimisation culture.

When we spar, there is an endless volley of apologies. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve inadvertently punched myself in the face. Ears are clipped, cheeks collide. It doesn’t seem to hurt. There are shouts of laughter. We stop, regroup, start again. Over and over. And over.

This endless awkwardness is exactly why boxing is like writing.

I instinctively recoil instead of slipping to one side to avoid a punch, and so stumble (boxing). I start second guessing, resort to further research, and get lost (writing). I duck too late and Sion’s pad grazes my temple – if this was a real fight, I’d be out for the count (boxing). I am flooded with self-doubt (writing). I wind my fist back and risk overbalancing (boxing). The centre of gravity goes (writing).

And yes, sometimes, there’s a moment – less than a second – of transcendence. When I forget to think, when I don’t even know my own name. And it feels amazing.

And then: time’s up. The shrill scream of the bright red boxing clock. My phone buzzes, 3pm, the school run. I let my gloves fall, then raise them back up for a fist-bump with Sion. ‘Very nice. Veeeery nice’ he grins at me. I love this man.

I’ve been wondering if it’s the idea of giving up awkwardness, and all its potential, that makes finishing a book so hard. When we are growing, anything is possible. The finished book or painting or song can sometimes feel like it has to be flawless and eternal. Dead, in Joyce Carol Oates version of the metaphor (or at least: no longer able to fight back, a TKO)

Right now, I’m trying to get this image of a boxer defeating her book out of my head.

Instead, I’m trying to think about the ending as just another moment. Another of those moments when you pause, sweaty and panting, with your stance all bent out of shape, and say: ‘this is what I think, right now’.